One email address for everything? A separate email address for every different service? Forwarders? Aliases? Spam? In this article, Mike Citarella takes you on an odyssey through the rough seas of email management, finding safe landing with his company’s own elegant solution in Bulc Club.

As developers, we rely on an email account to register and maintain online repositories, send and receive correspondence for projects we build and contribute to, promote and market this work through social media and other channels, and provide support lines for projects throughout their life cycles.

The more we rely on this simple communication tool, the more time we spend organizing and refining how we use it. We still share a personal email address with friends and family because we can generally trust them not to spam us. However, a work email address can easily get out of hand with the number of messages received (both wanted and unwanted) and the time and effort required to keep it organized.

It’s difficult to ensure that email helps make our work more efficient, rather than distracting and preventing us from being productive. At some point, we may all ask is there a more effective way of doing this? If you haven’t yet found your own solution, feel free to follow my Odyssean journey through the many approaches I’ve taken, so that maybe it will help you decide which is best for you.

One Address

The obvious starting point is the “One (or Two) Addresses for Everything” principle.

Some users might prefer fewer email addresses, with the understanding that one address is one inbox to check, and less overall work. They’ve got virus scanners and spam filters in place to help try and safeguard that single address, and hope that these counter-measures curb the abuse.

However, the convenience of one inbox may not outweigh the potential for catastrophe: if that single email address is exposed, and spam filters fall short, it can take a lot of work to rid the abuse or else shut it down and start again with a new, clean account.

Many Addresses

Others might prefer the opposite approach – separate and distinct addresses for each unique function – knowing that if one becomes compromised, it can be replaced with a new address without too much hassle.

This method is more controlled, isolating the address and making it easier to determine fault when it’s being abused. But it also increases the burden, with more inboxes to check.

Most mail services like Gmail or Outlook allow you to link accounts: logging into one inbox will also grant you access to the linked ones. This is a huge convenience for users who follow the many-addresses-for-many-things approach, cutting way back on the time required to log-in-and-out of many accounts and see what’s waiting for them inside.

Aliases

A third, hybrid model involves the use of aliases. Aliases are like photo tags, but for email addresses. They inform mail users of how they previously shared the address, and instruct mail services of automated measures that can be taken when these aliases are applied.

For example: myaddress@gmail.com has no alias, but if I share myaddress+github@gmail.com, the messages sent to this address will still arrive at the same inbox, but rules can be applied to add a label to them, color-code them, or move them to a folder. As long as those services that have my aliased addresses respect the aliases, I can theoretically treat an alias like a separate email address. I can even add filters that move messages to a spam folder (or delete them) if I’ve identified a sender as abusive.

Do senders respect aliases? Yes, usually. But I have also received mail tagged with aliases that I never created or shared. So it’s apparent some spammers have realized the simplicity of spoofing this useful mechanism and have used it to their advantage.

Forwarders

A forwarder (provided by a forwarding service) is another useful, albeit somewhat time-consuming, method of dealing with email. Forwarding services provide you with a new/unique address that simply forwards email to your real address. You can’t send mail from forwarders, only receive. These services are generally free to use, and they act as intermediaries between the senders and your actual address. The senders will never know it’s a forwarder unless/until you reply, as you’ll need to use your real email address to do so.

Forwarders are a more-or-less perfect option for the problem of sharing your address to potentially abusive senders, since they can often be individually switched off. Unfortunately, logging into the forwarding service to create, manage, and disable your forwarders can be cumbersome.

Now, my Odyssey

All things being equal, the Aliases method was the one I liked the best. So as an experiment, I created a new email address and began refining this homemade paradigm with aliases, inbox labels, and filtering. I may not yet be willing to admit it, but it’s quite possible that my behavior in the matter might have bordered on obsessive.

MyProjectEmail@gmail.com was where I started. I never shared this address. I only used it to log in to Gmail. Then, I started modifying all of my existing service accounts to use this new address, but with context specific aliases:

… and so on.

With Gmail filters, my mail all got labeled and sorted for me. I could read, reply and archive, directly from their appropriately colored mail folders. I knew I couldn’t reply using an email alias, but that didn’t concern me, since I was only using this workflow with services for which I needed the inbound mail – not the ability to send a response.

It was a thing of beauty. And I was impressed by the organization and happy with my work – for about two days. The flaws in my flawless system began exposing themselves right away:

- I wouldn’t be creating a separate Dropbox, GitHub, etc., for every project, so categorizing that mail by project wouldn’t be possible.

- Using aliases in any application that exposes the address also exposed the alias, meaning the address could be scraped, the alias removed, and the abuse untrackable and unmanageable. The whole email account would be compromised, and my elegant system of separating and organizing would fall apart.

I had been speaking to a number of friends in the development community about my hardships and received “a host” of solutions from each, based on their own idiosyncrasies and styles. Literally. They recommended hosting my own solution.

This involved purchasing a domain and tinkering with the mail service provided by my web host. Since server-side mail agents are equipped with what’s called a “Catch-All” (or a master mailbox that will “catch all” of the emails sent to my domain where I didn’t specifically set up an individual account), I could disable that option to greater reduce, but not eradicate, spam.

Then, with each new service, product, and support offering, I would log in to the server and create specific email addresses. These addresses could be simply deleted if they became compromised, and all future mail sent to that address would bypass the catch-all and be automatically discarded.

And while this solution seemed to solve all my needs, it also had a number of drawbacks:

- Like the forwarder method, I needed to create the addresses manually each time I needed one.

- To use an alias, I would have to forward mail to Gmail (or another alias-able email service) instead of using an address that showed my own domain.

- Each year I would need to pay to renew the domain and the mail server hosting account.

While I can justify the annual costs for this option, the time it took to create and manage the accounts was again almost as much of a burden as dealing with separate emails in the first place. Remember, my whole purpose for this pursuit was to maximize my workday and minimize time spent on email.

Hosting a solution also did nothing to thwart the potential for spam like a forwarder/intermediary would. Whether I’m using one address, many addresses, aliases, forwarders, or my own hosted email, I knew that once an address starts receiving junk mail, until it’s deleted, it will most likely always continue to receive junk. Basically, an odyssey that ends with a shipwreck.

There just didn’t seem to be a solution that simply said “here’s a way for you, and only you, to contact me, and if you abuse it, I’m taking it away.”

Finding Our Own Solution

The company I work for registered my exasperation and started working on its own solution.

The first draft was a basic approach – like a bit.ly for email addresses. Bit.ly, as you may know, is an online service that will help you take any link on the WWW and turn it into something compact and trackable. We started with that same concept and tried adapting it to email addresses:

- The email address: x30b11Aq7b2@address.com

- … would be decoded to: MyProjectEmail + service + github@gmail.com

- … which would be delivered to: MyProjectEmail@gmail.com … with aliases, labels, and filtered folders intact.

It worked, but it was ultimately scrapped for a better solution, because the encoded addresses were difficult for humans to share, and nearly impossible to remember. Spambots, on the other hand, had no issue with this. Disabling a compromised address quickly and easily was valuable, but we realized it was only one part of the solution.

The second part was making a “human” address that was both easy to create and share, but also immediately identified how it was being used. The bit.ly idea evolved to adopt some of the key benefits of the earlier-mentioned forwarder approach, where you’re not sharing your real address, but a forwarder that simply passes the mail along.

The new convention was as easy to remember as your own email address, but it also contained the alias right in front where you wanted it. Aliases could be made up on the spot, resolving the need to preset them beforehand, and the system would adapt to accommodate all new mail to the new address. Unlike Gmail aliases that could be removed, this new format required the alias to remain intact for the mail to be delivered.

github @ username . address . com

Our final solution: Bulc Club

Having found our solution, we naturally wanted to share it with others. And thus was born Bulc Club. It’s entirely free to use, too.

The idea not only worked, but it tested extremely well after we got over the hurdle of explaining it.

Because of how deeply we have become embedded in the old, static convention, the hardest part about the new approach was communicating how an email address wasn’t a fixed set of letters and often numbers, but one that changed shape when you needed it to – one that self-described how it was being used.

The shift in paradigm turned out to be quite difficult for my friends and family to grasp, and I learned it was often better to just describe Bulc Club in terms of how they will be using it.

How it works

We’ve tried to make Bulc Club really easy to use. Once you have set up an account, you never need to log-in, unless you wish to take advantage of the advanced features.

You can join up using your normal email address. Then, choose a username, like your first name, or a nickname – as if you were choosing a handle for Skype or another messaging client, for example. If you like “CuriousGeorge”, then use that as your username. You have just defined the unique structure for all of the forwarders you will create for your account:

____@CuriousGeorge.bulc.club

The account setup is complete.

Now, suppose you’re going to sign up for a service or a newsletter or anything, really, that requires a valid email address – your phone company, your grocery store, a survey or online contest, things like that.

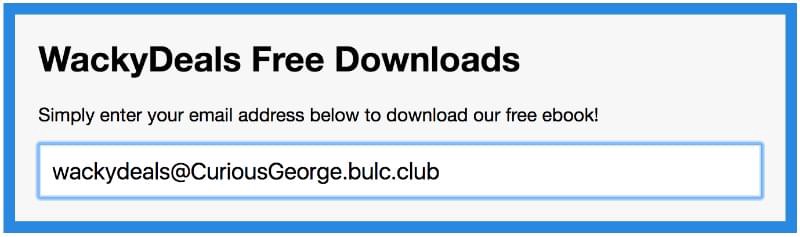

Instead of providing your actual email address, you can provide a unique Bulc Club forwarder. For example, to qualify for a free ebook from WackyDeals, you might use wackydeals@CuriousGeorge.bulc.club:

All messages sent to that address will be forwarded to your actual inbox. If you later find WackyDeals is misusing your address, you can eliminate it easily (as discussed below).

Of course, you can still use your actual email with your friends. But these online services don’t need to know your address.

Unique Features

Figure 01. Bulc Club members may even create multiple accounts, for example: to keep separate their business and personal emails.

Forwarding services like Bulc Club have popped up everywhere, as more and more email users discovered the same needs as I had when I first faced the problem. Some of them offered splinter features that set them apart, such as:

- self-destruct mechanisms, or limited lifetimes

- built-in virus scanning and content scanning

- pro/paid versions for self-hosted service, and vanity domains, etc.

Bulc Club doesn’t concentrate on these things, instead remaining focused on the ones that catalyzed the investigation into a solution. Bulc Club doesn’t require you to create your forwarders before use. You create them on the spot, as you’re signing up to something, and messages received at the forwarder will be passed along to your actual email inbox.

Additionally, you can log in to a private member console at members.bulc.club to see a history of all recent mail received by each of your forwarders, organized by date, sender, subject, forwarder, etc. From this interface, you can request individual messages be re-sent, disable forwarders in case they’ve begun to receive spam, analyze statistics on senders, and other things.

We don’t offer content-scanning. Privacy has always been a chief priority when scoping the service. Our “pro” version is the free version that comes with every new account, because we don’t intend for Bulc Club to be a source of income. We’re satisfied alone with running a service that solves this problem for its users.

Spam prevention

What does set our service apart is the spam prevention. It’s the safety-in-numbers maxim, but applied to the digital era. It’s folksonomy, where a tag from one person benefits everyone. It’s social networking, where our “like” button is actually a “block” button. Let me explain …

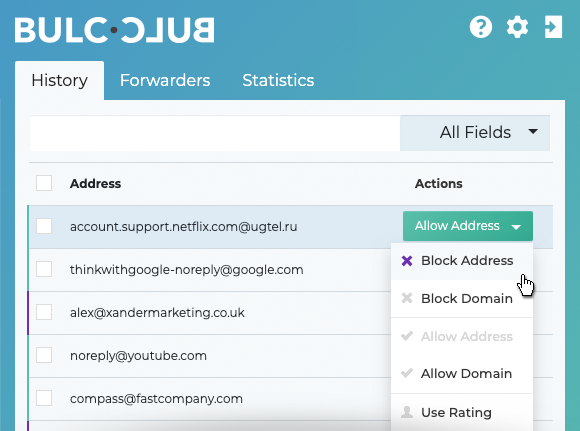

Figure 02. A small informational panel is added to the top of every message received in your inbox from your Bulc Club forwarder.

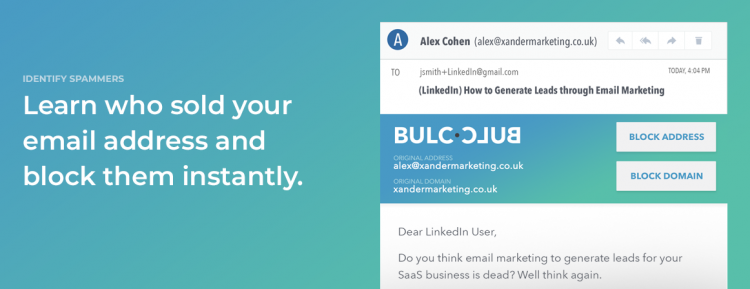

At the start of every email relayed to your inbox from Bulc Club is a small panel that details the properties of the message. This panel includes information about the sender and a link you can use to block future messages that come from the sender’s address or from the sending mail server itself. Bulc Club keeps a counter of each time a user blocks an abusive sender, informing other users of the potential a message has to be spam by these collaborative “ratings.”

Message senders and mail server domains that have sent spam in the past will likely send spam again. These two pieces of information might not only be common from message to message, but also from user to user. So any single user rating a spammy sender for their own benefit is in fact rating it for other users as well.

Just as Facebook pushes posts with the most “likes” to the top of your timeline, Bulc Club holds messages with the most “blocks” in a queue, undelivered. Users may actively request them to be delivered to their real inbox or passively let them be deleted from the queue on the server.

Every day, with every new member, these ratings become more accurate. This not only means that we receive less spam in our inboxes, but we also spend less time clicking the “block” buttons ourselves.

To explain this better, you might subscribe using a Bulc Club forwarder to a service that sends mail from myGreatService.com and you might also greatly enjoy the mail that they send you. Other Bulc Club members might also subscribe to that service and each time you (or they) get a message, the counter sees another consensual message to deliver. Then one day, some of these recipients start receiving mail from myGreatServiceMarketingPartner.com and, realizing they never asked for such a thing, flag the new sender as spam. Bulc Club will continue to deliver mail from myGreatService.com, but no longer deliver mail from this new domain to the users who blocked it. More valuably, these blocks also inform Bulc Club to possibly hold the mail from reaching you, depending on the rating the other members have given it. With this strength in numbers, it’s less work and time for each of us.

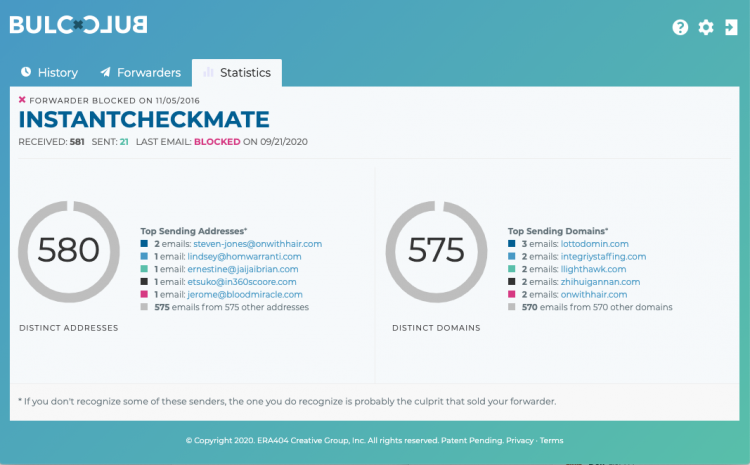

Figure 03. The Member Console shows you the counters that Bulc Club uses for the forwarders you create. This example shows addresses and domains for real mail sent to my InstantCheckmate forwarder.

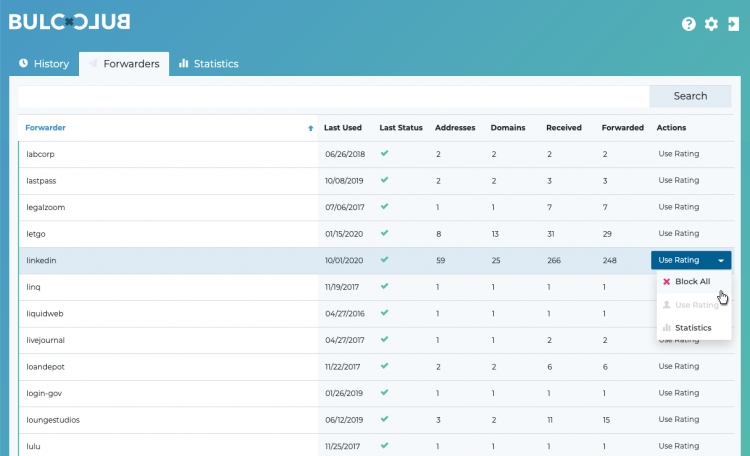

Conveniently, the panel added to each of the messages relayed by Bulc Club to your inbox contains links for blocking. You may never actually need to log in to your Bulc Club member section after creating your account. However, if you do, a history is provided of all of the emails received and which are being held (because of your blocks or a high member rating), and lots of other cool information about your account.

Figure 04. The Member Console’s History tab lists all of the mail received. The Forwarders tab combines all mail by forwarder and provides controls for handling the mail received through that forwarder.

Wrapping Up

One of Bulc Club’s earliest adopters shared with me how he uses the service:

In my opinion, it’s just as vital as my password manager. If one site I use gets hacked, my private email isn’t leaked, just the forwarder. Just like how if you use a site with a randomly generated password, all your passwords won’t get leaked and your accounts are kept safe. Plus I haven’t had spam in ages. – @MikeColeDotCo

In short, Bulc Club is a rather creative solution that combines:

- the distancing of real addresses from potentially abusive senders with forwarders

- the efficiency of creating and disabling these forwarders

- the collaborative spam prevention of an entire network of users

- the guarantee of a service designed to protect privacy

- the reasonable cost: Free. Always.

It is our belief that this model will not only set us apart, but protect your inbox and ultimately, one day, rid the world of spam altogether. And all this was born from the goal of making email (the occupational burden we all battle daily) once again a non-issue, so that everybody can go back to doing the things that we enjoy – in our case, reading SitePoint articles and building cool things. 🙂

Mike Citarella is the lead developer for ERA404 a design, development, and strategy studio based in NYC, and a founder of Bulc Club. This article was originally published on August 21, 2017 on SitePoint.com.